July 10, 2010 – November 4, 2010

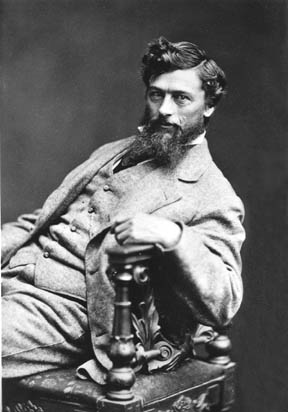

Image: Merk Oliver (Yurok) tending the salmon roast at the Yurok Salmon Festival in Klamath on August 20, 2006. Photo by Ira Nowinski.

“My mother told me this when I was young. I didn’t understand what she meant then, but I do now. She said we had many relatives and we all had to live together; so we’d better learn how to get along with each other. She said it wasn’t too hard to do. It was just like taking care of your younger brother or sister. You got to know them, find out what they like and what made them cry, so you’d know what to do. If you took good care of them you didn’t have to work as hard. Sounds like it’s not true, but it is. When that baby gets to be a man or woman they’re going to help you out.

You know, I thought she was talking about us Indians and how we are supposed to get along. I found out later by my older sister that mother wasn’t just talking about Indians, but the plants, animals, birds – everything on this earth. They are our relatives and we better know how to act around them or they’ll get after us.”

Lucy Lozinto Smith, Dry Creek Pomo

Sherrie Smith-Ferri, Director of the Grace Hudson Museum, curated this exhibition in consultation with her aunt, Kathleen Rose Smith. Smith-Ferri noted how much fun it was to put the exhibit together. “It brought back lots of good memories of getting together with the family to spend time at the coast harvesting abalone, mussels and seaweed, or going to pick berries. And of course, it brings back recollections of some great meals eaten together. I found I would get really hungry if I worked too long a stretch of time on the exhibit.” After its Ukiah venue, the exhibit will travel for more than three years to other museums throughout California under the auspices of Exhibit Envoy (formerly the California Exhibition Resources Alliance). Funding for this exhibit was provided by the Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians, the Mendocino County Office of Education, the California Exhibition Resources Alliance, and the Sun House Guild.

Before the coming of the Europeans, the land now known as California supported more than 1000 independent bands, tribes, and nations. Many of these peoples lived in the same small areas for thousands of years without feeling the need to move on. Such long-term rootedness was possible due to the knowledge, respect, and restraint with which Native Californians approached plants and animals that sustained them. Strict rules governed their interactions with the environment: they gathered plants only at certain times; they burned, pruned, and dug in prescribed ways and at carefully calculated times, and they gave something back for whatever they took. The “untrammeled wilderness” the Europeans thought they discovered was in fact a carefully managed ecosystem.

“Our foods were (and still are) as varied as the landscape, as are our methods of preparing them,” states Smith. “We ate them raw. We roasted, boiled, baked, leached, steeped, dried, and stored them, and, after contact, we fried, and canned them.” The book and the exhibit contain harvesting instructions and recipes for many delicious foods, including Huckleberry Bread, Pine Nut Soup, Rose Hip or Elderberry Syrup, Peppernut Balls, Roasted Wood Rats, and Ingeniously Roasted Barnacles. Barnacles were roasted by the Pomo by building a fire right on top of a bed of barnacles at low tide. The barnacles would cook until the incoming tide would extinguish the fire and cool the meal. The barnacles would be eaten the next day.

“Seaweed, Salmon, and Manzanita Cider” easily avoids romanticizing the “good old days,” however, by comfortably and sometimes humorously weaving in the realities of modern times. After giving a richly detailed description of her family’s traditional and extremely labor-intensive methods of gathering, storing, hulling, pounding, leaching, and cooking acorn, Kimberly Stevenot (Northern Sierra Mewuk) reminds her readers, “But let’s face it folks, this is now. Today, (you can grind) small batches (using) an electric coffee grinder, and a mill and juicer work wonders for medium batches. For large batches like my sister and I make, we use an electric flour mill.