JOHN HUDSON

Grace Hudson’s husband, John Hudson (1857-1936), was born into a prominent family in Nashville, Tennessee; the youngest, and only son, out of seven children. The family expected that he would become a doctor, like his father. John attended the Western Military Institute at Nashville University, and went on to medical school at Nashville Medical College, specializing in homeopathic medicine and gynecology. He began his career as a homeopathic physician in Kentucky, then returned to Nashville where he continued his practice for several more years. In 1889, shortly after his father’s death, he emigrated to Northern California having secured a position as physician for the San Francisco and North Pacific Railroad that now had its terminus in Ukiah, Mendocino County. Shortly after his arrival in California, John met and courted Ukiah artist Grace Carpenter Davis, a recent divorcée. John and Grace were married on April 30, 1890. His mother and sisters in far-off Nashville, were somewhat dismayed as they had hoped for a more conventional partner for him. However, the couple had a similar outlook on life and shared a passionate interest in American Indians that became a lifelong bond between them.

Hudson had participated in various archaeological excavations in the Mississippi Valley region, and once in Ukiah, he became increasingly interested in the local Pomo peoples to whom he was introduced by members of the Carpenter family. As his studies of Pomoan languages, culture and basketry occupied more of his time, John’s medical career languished. Hudson gave up his medical practice within five years of his marriage to Grace Carpenter Davis, and spent the rest of his life as a collector-scholar, amassing significant collections of California Indian basketry and other ethnographic artifacts. His reputation as an excellent amateur anthropologist led to his 1901 appointment as assistant ethnologist in the Department of Anthropology at the Field Columbian Museum of Chicago. In this capacity, John spent five years traveling throughout remote regions of California, collecting artifacts, taking photographs, and recording cultural and linguistic information from a multitude of California Indian peoples. After a disagreement with his supervisor, Hudson resigned his position and in 1906 returned to Ukiah. There he spent the remainder of his life independently pursuing his own ethnographic studies, culminating in a 900-page opus on Pomo Indians, unpublished at the time of his death. His significant basket collections are prized today at the Smithsonian Institution, the Field Museum in Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Grace Hudson Museum in Ukiah. The extensive manuscripts and correspondence of John Hudson form the heart of the Grace Hudson Museum’s research collection.

AURELIUS ORMANDO CARPENTER

Aurelius Carpenter when Grace was in art school.

Born in Townshend, Vermont, Grace Hudson’ s father, Aurelius Ormando Carpenter (1836-1919) was the third child of Justin and Clarina Carpenter. Called “Reel,” or “A.O.,” he had newspaper ink in his veins: his father, mother, (and stepfather) were all newspaper writers, editors and publishers. After completing his basic schooling, and apprenticing at the Windham County Democrat in Brattleboro, Vermont, Aurelius moved with his family to Kansas Territory in 1855. The following June, he fought alongside revolutionary abolitionist John Brown at the Battle of Black Jack. While recovering from wounds received in the fight, A.O. was tended to by neighboring “free state” women, including a young teacher named Helen McCowen. This bonding experience led to them marrying six months later. In May of 1857, with members of Helen’s family, the newlyweds journeyed across the plains by oxcart to Grass Valley, California, to join Helen’s brother who was mining there. Eventually settling in Potter Valley, in Mendocino County, Aurelius ranched and Helen taught school. The Carpenters’ twins, Grace and Grant, were born in Potter Valley in 1865, joining an older sister named May. By this time, Reel had helped publish the county’s first newspaper, the Mendocino Herald, which he also co-owned. Over the next three decades he worked as printer, publisher, and editor of a number of newspapers, including the Ukiah City Press and San Francisco’s Fair Daily. Due to the demands of Aurelius’ many business responsibilities, and in an effort to supplement his meagre ranching income, the Carpenters left Potter Valley in 1869 to settle in Ukiah, the county seat. Their final child, Frank, was born there in 1870. In Ukiah, A.O. established the “Home Gallery,” a photography studio that catered to white and Pomo Indian customers alike. He and Helen ran this family-owned business for more than 40 years. An important pioneer photographer, A.O. traveled all over Northern California recording “views” and taking portraits. During this same period he was active in civic affairs, and at the end of his life authored a history of Mendocino County, a role which half a century of enterprising residence had well prepared him to undertake.

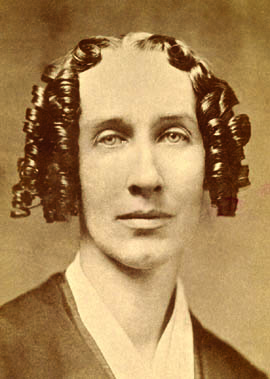

HELEN MCCOWEN CARPENTER

Grace Hudson’s mother, Helen McCowen Carpenter (1838-1917), grew up in Indiana and when a teenager graduated from the Bloomingdale Quaker Academy with a teaching credential. In 1855 Helen moved with her family to Kansas Territory, where she began her professional career at age 17. Kansas was in political turmoil as it prepared to enter the Union, and the McCowens, who were staunch abolitionists, worked to make it a “free” state rather than one that allowed slavery. Helen met her future husband, who was also on the abolitionist side, when Aurelius Ormando Carpenter was wounded fighting for the free-state movement at the “Battle of Black Jack,” an altercation that is now considered the first military engagement leading up to the Civil War. After helping nurse Aurelius to health, Helen and he married on Christmas Day in 1856. Five months later the newlyweds traveled west to California in an ox wagon train with Helen’s parents and other family members. Helen was four months pregnant with her first child when they arrived in Grass Valley, California, in October 1857. Within two years, the Carpenters and McCowens had moved further west to Potter Valley in Mendocino County, where other relatives were already settled. There Helen became the first teacher certified by the new County Board of Education, and worked as an educator for the next decade.

Helen Carpenter c.1900-1910

In 1865, Helen gave birth to twins Grace and Grant, who joined their elder sister, May. Seeking more opportunity for economic viability for the growing family, in 1869 the Carpenters relocated to Ukiah, the county seat. There they established a photography studio, where Helen assisted her husband, “A.O.,” by running the studio, and taking portraits, during his extended work-related absences as a newspaperman and traveling photographer. In addition, she spent her days caring for their children, the last of whom, Frank, was born in 1870. She also contributed enormously to Ukiah’s civic and fraternal life, blessed with endless energy and admirable executive ability. In particular she was very active in the Order of Eastern Star and the Rebekah Lodge, and helped establish churches, a social club, and the library within her new hometown. Beyond her teaching and organizational skills, Helen was talented as an amateur artist and fine musician. She instilled a serious appreciation for the arts in her children, and was quick to encourage their creative abilities. Her admiration for the beautiful basketry of the Pomo Indians led her to become a respected Pomo basket collector; an avocation she passed on to her daughter Grace, and son-in-law John Hudson. A prolific writer, whose work is now enjoying increased recognition, Helen wrote and published articles and stories on the customs and history of the local Pomo Indian peoples, and early pioneer days in Potter Valley and Ukiah. She even dabbled in poetry, advertising jingles, and songs. Grace recalled that her well-rounded mother was “one of the belles of early California . . . beautiful and accomplished with sparkling intelligence.”

CLARINA NICHOLS

Grace Hudson’s paternal grandmother, Clarina Irene Howard Carpenter Nichols (1810-1885), was the first born of eight children, and grew up in West Townshend, Vermont. At age fourteen she exhibited the keen mind and determination that were lifelong hallmarks of her character, when she avowed that she would rather have advanced schooling over a “setting out in the world,” or dowry. Her father did eventually send her to a “select school” in West Townshend for further education, after which she taught for a year or two. At age 20, Clarina married Justin Carpenter, a recent law school graduate and member of a prominent local family. The young couple moved shortly thereafter to Brockport, a boomtown on the Erie Canal in western New York state. There Justin became active in civic life, opened a secondary school (the Brockport Academy), and published a temperance newspaper. Clarina is thought to have taught at the Brockport Academy, but also soon bore three children including Grace Hudson’s father, Aurelius Ormando Carpenter. Justin, through a combination of bad luck, dour temperament, and poor business skills, floundered at his various enterprises and Clarina was increasingly called upon to contribute financially. After years of a deteriorating relationship and emotional abuse, Clarina separated from Justin in 1839, and returned with her children to her parents’ home in Townshend. Turning to writing as a way to support herself, she became acquainted with George Washington Nichols, a widower more than 25 years her senior and the publisher of the Windham County Democrat in nearby Brattleboro. In 1843, Clarina was granted a divorce from Justin and she quickly married George. Within a year Clarina had born her fourth child, George Bainbridge, and was quietly running her husband’s newspaper behind the scenes, as his health failed him.

The newspaper gave Clarina a forum to express her growing support of current social reforms, in particular those of temperance, abolition, and women’s rights. She now began organizing women’s rights conventions throughout the east, and was a much sought-after speaker. In 1852 she became the first woman to address the Vermont State Legislature, where she urged the passage of a law that would permit women to vote in district school elections. At this time she also began a friendship with women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony, that would last the rest of her life. Several years later, Nichols and her family joined the “free-soil” emigrants settling Kansas Territory, in part to work towards a government of “equality, liberty, fraternity” for women and blacks in the state-to-be. However, her weakened husband died within a year of their arrival, and son Aurelius left for California with his wife’s family in 1857. Despite these losses, Clarina worked tirelessly for the causes of abolition and women’s rights in Kansas. Briefly relocating to Washington, D.C. during the Civil War, she was employed as the matron of a home for freed slave orphan children. Meanwhile, largely due to Clarina’s efforts, when Kansas entered the Union as a free state in 1861, its state constitution granted women the freedom to control property, share custody and vote in local school elections.

At age 61, Clarina migrated to Potter Valley with her youngest son George, his Wyandotte Indian wife, Mary, and their three children. Son Aurelius and his family were not far away in Ukiah. After Mary’s death in 1873, Clarina helped raise George’s children, while continuing extensive writing campaigns supporting her many causes. She remained a nationally recognized voice for women’s rights throughout her latter years, and in truth paved the way for many of the civil liberties that women in this country now enjoy.